Ronald M. Helmer

Memoirs of a Worldly Guy

Lew

Elaine had written to tell me that a yacht called the 'California' was in the Ala Wai Yacht Harbour, planning to sail to Tahiti, and short of experienced crew. I flew to Hawaii within a couple of weeks. When I arrived in Honolulu I proceeded directly to my old quarters on Kealohilani Avenue. Yoonch greeted me with pleasure and I was awarded the 'Royal Suite', the only room with an electric refrigerator. It cost a dollar more... $13 a week! The missionary girls had moved to a suite of rooms on the Diamond Head side of Kapiolani Park near the Aquarium. I dropped in to say 'Hello!' and spent the next few days skin-diving from the jetty in front of their apartment. It seemed very pleasant to be back in the islands.

In a day or so I wandered down to the yacht harbour and located the California. To my surprise I found there was no skipper aboard. I gathered that he had returned to the mainland, either to get his wife, divorce his wife or to get married, I was unable to ascertain. After all, his boat was called California! There were, however, some members of the crew still aboard. One crewman had apparently refused to leave his bunk during the entire nineteen day crossing from Los Angeles to Honolulu. I'd heard of seasickness but that was ridiculous. He was no longer in evidence.

Although the boys on board invited me to move in with them, I decided to wait until the skipper's return from the mainland before taking such a liberty.

Lew had taken three years of journalism before starting his hitch with the Navy. Now he was spending his time with the Navy's Department of Public Relations. One evening he asked me if I would like to go to the annual memorial service held on the deck of the U.S.S. Arizona at Pearl Harbour.

'I'd like very much to be there,' I said.

'I'll see what I can do,' Lew said, 'but don't bank on it. So far as I know they've never allowed anyone but Americans to be present.'

I was carrying a letter from the City Editor at the Calgary Herald authorizing me as a correspondent and Lew was banking heavily on this to turn the trick. A few nights later I had a phone call from him.

'You'll never believe this,' he said, 'this thing's been all the way to the Pentagon and back. Public relations here had to clear it with navy security. Apparently they even got the F.B.I. into it before they were finished.'

'Look,' I said, 'if this thing's going to put you on the spot...!'

'No strain,' he said, 'it's all cleared now. Be at the gates at Pearl Harbour tomorrow morning at seven o'clock. I won't be allowed in myself but a girl friend of mine from the P.R. section will meet you and take you in tow.'

I was in place in good time the next morning and boarded a navy tug with about forty others. I noticed a few of Japanese ancestry among them. The tug cast off and we churned out into the harbour past giant cranes and cliff-sided aircraft carriers that dwarfed our craft. When we reached the projecting mass of crumpled steel that was the bridge of the Arizona, the tug throttled down and bumped against a ramp. A group of people carrying wreaths stepped onto it from our boat and walked slowly up to the bridge as the ceremony began.

The office of naval records and history, ship's histories section of theU.S. Navy Department, recording the history of the U.S.S. St. Louis, reads in part:

The date was December 7th, 1941. Most of the strength of the American fleet was under attack.Her engines were cold and her crew was carrying out holiday routine. At 07:56 two of the ship's officers observed a formation of dark-coloured, unfamiliar planes approaching from westward over Ford Island. General quarters were sounded immediately and the crew manned battle stations at the double...

Thirteen years later, to the minute, we stood on the bridge of the U.S.S. Arizona, observing a ceremony commemorating those who died in one of the blackest days in American history.

As the bugler played the last notes of 'Taps' we looked beyond him to the burned and twisted cylinder of tortured steel that was once No. 3 gun turret mount. To one side, rising like grotesque brown mushrooms from the oily surface of the dirty water were what served once as ventilators, showing the ravages of weather and corrosion as nature finished the destruction begun so tragically many years before.

We stood on a special wooden platform built to provide safe footing on the deck plates, now crumpled and twisted like a cardboard toy thrown aside by a peevish child. As the sad ceremony proceeded, mothers and sisters laid wreaths at the foot of the mast in memory of sailors entombed below our feet. A stocky bo's'n's mate stepped forward and placed a wreath among the rest then stepped back smartly and held a long salute. The ribbon on the wreath said 'Well done, shipmates!' I doubt that there was a dry eye in the gathering. I think I felt at that moment, some of the tremendous emotional strain placed on these representatives of the many bereaved families of the men below.

U.S.S. Arizona died in only eight minutes. Eleven hundred and fifty-nine Americans went to share her coffin. It seemed strange to realize that these first Americans to die in the greatest of all America's wars never knew they were in a Second World War. Just a few agonizing minutes of smoke and fire and frantic, pointless pain with no warning and no explanations made.

It was something considerably more than a statistic to me now, however, and no longer just a casualty list in a sunken ship in a place I'd never seen. Now I was standing on the bridge of a shattered ship that had been manned not by statistics, but by men. Some had been just like the gobs standing at attention by the mast now, doing a job in a white duck uniform and wondering what might turn up to break the monotonous routine of navy life. Well, something turned up all right...

The history of the St. Louis reads...

...the crew was carrying out holiday routine...

These were all guys with lots of things left to do in life and not much time to do them. A few had probably roamed around Hotel Street the night before, some just kids in lonely groups, away from home, but wishing they were back. They had less time than any of them had thought when they hit the sack on the night of December 6th, 1941.

There will undoubtedly be many more wars and many more senseless deaths. About all one could do was think of them for a few minutes every year, and if you happened to know one of them you could stand on the bridge of the Arizona and remember for a while.

I was shooting movie footage at this time and found myself handicapped by lack of transportation. I looked at some pretty weird rolling stock before I settled on a 1952 Buick convertible owned by a young American Air Force couple whom had been transferred back to the mainland. I paid them five hundred and fifty dollars cash. The chrome showed a touch of rust and the blue paint job was a little the worse for the salt water mist in the air, but the automatic top worked fine and I figured I had a good deal for a car two years old. As I shall disclose later in this narrative, however, this seemingly innocent transaction was ultimately to assume aspects of skulduggery and intrigue that leaves me wondering to this day.

In 1953, Ron shipped his Buick to New Zealand as he continued his travels. In this photo Barry Crump tries out Ron's "flash pakeha" convertible prior to having the steering wheel moved to the opposite side in order to comply with New Zealand regulations.

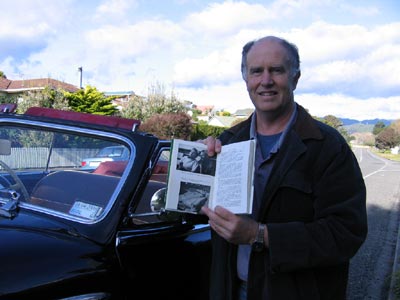

Fast forward 55 years to 2008 and Dave Peters who is the current owner of Ron's Buick. Here, Dave poses with the car and a copy of Ron's book, 'Stag Party'.

A close-up photo of Dave Peters with his copy of 'Stag Party' opened to the page showing the photo of Barry Crump sitting in the Buick.

This new piece of equipment lent great flexibility to my operations in and around Honolulu. For example I was able to spend time filming the activities of the surfboarders on the other side of the island without having to camp in the vicinity.

The mahogany-coloured beach boys at Waikiki would get a bit restless at this time of the year. They would stir uneasily during conversation and sniff the air with a faraway look in their eyes, like possum dogs on a full moon night. People who have witnessed this phenomenon in the past will tell you it's a sure sign there are big waves at Makaha. Every year, when the surf peters out at Waikiki and the ocean lies flat as a mill pond as far as the eye can see, the 'board' men pull up stakes and head for Makaha.

For one who has never seen what the Pacific Ocean can drum up in the way of sea swells, and then is suddenly confronted by the awesome green 'growlers' that roll in at Makaha, it seems inconceivable that there are men who will involve themselves with these liquid mountains.

Leaving Waikiki's beach hotels behind, I would drive through Honolulu Harbour, my route curving past Pearl Harbour and into the green sugarcane fields of Ewa and Waipahu. Then I would cut north again and drive for miles along the foaming white fringe of the Pacific. Cruising through Nanakuli and Lualualei whose inhabitants were mostly pure Hawaiians, I would have to slow down to miss the swarms of beautiful dark-haired children trooping along the roads to school.

Ninety minutes and some forty-five miles from Waikiki, I would round a steep bluff of reddish-brown volcanic rock and stop the car in the grass beside a curving crescent of perfect, tan-coloured coral and hear the deafening roar of the great waves smashing themselves ponderously against the steeply sloping beach. The peculiar, funnel-like nature of the cove at Makaha seems to emphasize the action of the mighty, heaving swells as they glide in, shoving them up to heights in excess of twenty-five feet before the racing undertow streaming out from shore trips them up and they fall face forward in the foaming surf.

Then your eyes widen in amazement as the next monster in the set begins to 'peak up' a hundred yards or more from shore. The bobbing black thing you mistook for a coconut develops madly threshing arms and you realize it is a small boy body surfing. Some unseen force propels the arched brown form to the crest of the towering wave and you are treated to the amusing sight of a curly black head and hunched shoulders protruding from the face of the wave, suspended above a watery chasm as surf and surfer race with express train speed toward you. Then when the wave begins to break over and the destruction of the foolhary youth seems imminent, the intended victim somersaults quickly forward and disappears with the flick of a green-flippered foot, to emerge at the back of the wave a moment later, clear of the vicious maelstrom of sand, surf and broken coral churning just ahead.

Still farther from shore, a group of 'sliders' sit bobbing on their boards like a flock of sleeping ducks, waiting for a wave that suits them. Then, suddenly, as if at a given signal, they fling themselves forward and lying prone, paddle furiously, shooting forward as the wave tip catches them. When their speed matches that of the wave, they make a smooth, effortless bound to their feet and go racing across the face of the great green wall at breathtaking speed. As in skiiing, some fail to make it and are lost in the cataract as it breaks over them. A long swim shoreward usually ensues as they attempt to recover their careening board. In a strong rip tide boards sometimes drift far down the coast, as their hapless owners flounder in pursuit.

Compared to skiiing on snow, the sport of surfboarding seems to have both advantages and disadvantages. For one thing, water is a much more yielding substance. On the other hand, a ski slope is a solid, dependable sort of business, never indulging in such forms of treachery as sneaking up from behind and hitting you when you are not looking. In surfing, particularly in deeper water, the ability to swim presents itself as a decided advantage. Without it, the beginner seldom lasts long enough to acquire any appreciable degree of skill. In skiiing, of course, the non-swimmer may assault the slopes with impunity, excepting in very warm weather, when puddles may form.

Like most other sports, surf boarding has its ardent amateur devotees. Not being given to prissy euphemisms I shall henceforth allude to these good boys as 'beach bums'. In those days Waikiki harboured some very colourful characters. There used to be a little lunch room just next to the Fisherman's Wharf. There were blue and white umbrellas placed over tables where the 'in' types met of a morning to consume banana pancakes prior to doing a day's battle with the big waves. Two of the boys I met here were natives of California, wizards of the Malibu board, whose names were also All-American; Bob and Al.

'Meet the man called 'Purple'!' Bob said to me one morning. 'Purple' left his stack of banana hots long enough to meet me; he was colourful in more than name. He wore a straw hat a size too small with a flower in it a size too large. His dark skin actually shaded into deep purple in places and it covered a torso that indicated no weight problem. One pancake makes most people fatter but four of these characters would get the short order cook up an hour before the doors opened and walk away after devouring mountains of pancakes with their size 30 shorts still hanging slack. A row of quart sealers filled with a murky grey liquid prompted an inquiry on my part.

'Beef and barley broth,' said Al. 'We have that for lunch.'

'That's it?' I asked.

'Sure! You don't feel too hungry when you're surfing anyway,' he replied, 'and there's plenty of mileage in that brew!'

In spite of the fantastic amount of energy expended by these boys in six or seven hours on the boards, I could understand it after all. Any self-respecting Eskimo would have gone to sleep for at least three days after tangling with the quantity of carbohydrate that Purple had just demolished. But these gustatorial matinees were mere bagatelle. It was when the lads returned from their daily exertions that they established themselves as trenchermen of stature.

'We'll go to the Waikiki Sands' they'd say. 'Buffet deal, like smorgasbord, you know, all you can eat for a buck!'

Our arrival was obviously of no consequence to the hat check girl when we entered, for she welcomed my companions with a warm and ready smile. The effect on the manager was somewhat jarring however. 'Well, there goes another week's profit,' he said with an air of resignation, as we approached the groaning board.

I watched in quiet disbelief as my companions loaded their plates with layer upon layer of food from the trays before them. Nothing escaped the rapier-like thrusts of their forks. When the mounds of victuals had assumed the rough outlines of African anthills, some of their selections began slipping back to the table.

'I believe you've exceeded the 'angle of repose'!' I told Al, 'you'll either have to put up a retaining wall, or else come back for another load.'

'Damned plates are too small!' he complained.

'Twelve inches across does seem tiny, doesn't it?' I said sarcastically. My wrist was starting to ache from the weight of food it was supporting. We found a table and sat down. The boys ate with silent intensity; their portions seemed to melt away like spring snowdrifts as they settled into stride. I was about halfway through my modest helping as Al put the finishing touches to his first load.

'Reasonably tasty!' he said as he left the table, plate in hand. 'I might try a teensy bit more!'

'Fantastic performance,' I observed to Bob, 'I wonder where he puts it all!'

'You haven't seen anything yet,' replied Bob, who was lagging only a few mouthfuls behind, '...the boy's just warming up!'

As Bob headed back for seconds Al returned with a plateful that was indistinguishable from its predecessor. He bent his head and swung once again into his practiced rhythm. I began to watch for signs that would indicate a slackening of pace, but he neither flagged nor failed; the deglutition continued apace. I realized at last that I was in the presence of a true gourmand in the fine old tradition of Diamond Jim Brady and Henry VIII. I sat back in respectful silence and watched the performance.

'You think this boy can eat,' said Bob, recently returned with his second truckload, 'you should see the man called Purple go to work when he's in training. There's a place out there that has seventy-two ounce steaks with all the trimmings...it's yours free if you can knock it back in an hour! Purple couldn't afford to chance it himself so a guy who wanted to take some movies of a champion at work put up the money.'

'You mean he filmed the whole event?' I asked.

'Not all of it, but he had his lights all set up and filmed the highlights in colour, no less!'

'Did Purple beat the time limit?'

'You might say so,' Bob said, 'he breezed through everything they served him including a double banana split for dessert. When he finished they found there were ten minutes left. After a certain amount of embarrassed humming and hawing Purple asked the manager if it would be all right if he had another banana split!'

'I'd really like to see him at the peak of his form some day,' I said, turning to Al. 'Do you think you could cross forks with him and hold your own?' I never got an answer...he had gone back for 'thirds'!

My social life at this time bordered on exuberance. Gene Good had a radio sports program each evening at six o'clock called the 'Primo Penthouse'. Primo manufactured the local beer and sponsored the nightly broadcast from the penthouse situated at the top of the brew house in downtown Honolulu. About five-thirty each afternoon I would climb into the Oldsmobile and set off for the penthouse. A famous hit tune of the day was 'Mr. Sandman' sung by the Chordettes. It remains to this day one of my favourite popular tunes, and whenever I hear it played I am transported in my mind's eye back to Kapiolani Boulevard where I am cruising along without a care in the world, in my open convertible, licking my lips in anticipation of my first long cool draught of Primo.

Gene usually had a sports figure or two on hand for an interview. Wrestling was very big in Honolulu in those days. Mike Karasek was the local promoter and I reminded him one night that I had seen him a quarter of a century earlier wrestling in Calgary's old livestock pavilion during his salad days. He had been involved in what was called a 'wrestle royal'. Six wrestlers got into the ring to start the evening's dramatic presentation. The first two uglies thrown from the ring were matched together later and so on as the bodies flew in progression through the ropes.

Mike had more hair on his back than most men have on their heads. As a then current villain of the Calgary wrestling scene, he was singled out for a piece of gang play with one husky on each of his arms and legs, while the fifth sat on his back and pulled out large handsful of hair after the fashion of a naughty child pulling the stuffing from an old sofa. With each tug Mike would rise screeching into the air. When his tormentors tired of this diversion they lugged his tortured body to the ropes and threw him overboard. When I brought up the subject at the Primo Penthouse, Mike changed the subject to cooking and reminisced about some more appetizing and less painful recollections concerning culinary accomplishments.

Lew Teeter would make a brief report on the American football scene and I would follow with a few words about pro football developments in Canada. Later on Lew and I would go to one of several bars that were scattered along the boulevard between downtown Honolulu and Waikiki. One night we saw a tremendous red glare in the sky. There was storage yard on fire and the police had blocked off traffic for miles around. We parked the car and after dodging down alleys and between buildings for about ten minutes we got close enough for a good view. This was truly a fire of impressive proportions. Large stockpiles of rubber tires and drums of oil were sending flames hundreds of feet into the air and dozens of firemen were working close in to the fire that spread over a large area.

'Let's get a closer look!' Lew said.

'Capital idea!' I said, 'how do you propose to get past the line of harness bulls I see guarding the landscape?'

'Have no fear!' he replied, ' the members of the fourth estate are not to be deterred!' He reached for his wallet and took out a couple of cards. He handed one to me as we reached the line of officers.

'Sorry gentlemen, this is as far as you go!' said one of the 'happiness boys' as we came up to them.

'Press!' said Lew, holding out his card. The policeman glanced at it. 'Okay!' he said, waving Lew past.

'Press!' I echoed, elbowing past.

'Just a minute, buddy. Let's see the card!' said the cop, grabbing my arm. I handed him the press card Lew had given me.

'Well, whadda ya know? Arkansas Traveller, eh? You're a long way from home, aren't you, buddy boy?'

I thought for a moment. Arkansas Traveller? I certainly was a long way from home. Up until a few moments ago I had been a Canadian. But a man has to be adaptable.

'Ah purely am, suh, Ah purely am!' I said, taking my card and walking after Lew. We walked across the field until we were within a hundred feet of the blaze. Firemen running back and forth were silhouetted against the bright flames as a captain shouted orders to them. The chief of the Honolulu Fire Department stood beside him. We joined them.

'Hi, chief!' said Lew. The chief glanced our way and nodded.

'Bad one, eh?' I said, assuming my gravest journalistic mien. The chief grunted and turned back to his captain.

'I just been talking to the chief,' I said to Lew.

'That right? What'd he say?'

'Says it's a bad one!'

We stood together for a few moments nodding our heads sagely toward the conflagration. The responsibility of our positions weighed heavily upon us. After a while we walked back to the car and drove over to the Shangri La for a glass of rum--or a mint julep.

-o-

Deny eventually showed up on the 'Oronsay' of the P&O line and we made plans to sail on to New Zealand together. When Deny and I left for New Zealand I decided to prepare a 'going-away' dinner for my Hawaiian friends. I went to a supermarket and bought spaghetti, tomatoes, tomato paste, hamburger meat, onions, celery, garlic, bread sticks and so on for a bang-up 'spag' and meat sauce feed. Don't worry, I didn't forget the red wine and laid in an adequate supply; three gallons!

Bill Boyar was one of my University buddies interning at the hospital in Hawaii and I borrowed his car and used it for transportation when buying all of the supplies for my going-away party (at his and his wife Doris's flat!)

'Gosh, it looks just like a gravel pit in there!' Bill had said when I went to him at the hospital after my skin diving mishap at Hanauna Bay. 'How did you manage to do that?'

'I shot my Hawaiian spear at a fish and missed. I could see my spear sticking out of a coral head and went down after it. My ears started to hurt but I figured I could reach it with one more kick of my flippers. I guess that was one too many; I heard a loud squeaking sound and I guess that was the old ear drum bursting. I've felt like I had a garbage can over my head for the last two days.' Bill flushed out my ear with sterile water and treated it with an antibiotic and happily the drum healed. Subsequent examinations barely revealed the suture.

I assume the 'going away' party was a success. I admit that I got drunk; I ended up on the 'Oronsay' with the cabin full of my friends, wearing the 'grass' skirt from one of the Kapiolani hula girls who accompanied Lew Teeter. After all of those 'going ashore that's going ashore' had been herded on their way I set out to do a spot of onboard visitation. In my inebriated state I decided it made a great deal of sense to pay a social visit to the ship's captain. Fortunately I was intercepted by some junior officers after playing poker with the crew in their quarters en route to my visit to the captain and saved the inconvenience of a night in the brig. I spent two days in bed recovering from my hangover.

Bill Boyar grumbled that I had left Hawaii with the keys of his car in my pocket. He returned to Calgary in due course and at the time of his retirement years later was Chief of Staff at the Rockyview Hospital in the south of town.

'Even the sleaziest of hotels have a manager who checks the register occasionally,' I chided him when he discovered I had been in one of the beds for two weeks before he became aware that I was there. I had my legs crossed and he reached over and uncrossed them as he left. That was the last time I saw him. Two weeks later he decided at the last moment to join some old buddies in a pheasant shoot and shot himself instead. His wife Doris committed suicide a few months later. They'd had more to worry about than crossed legs.

�— The End —